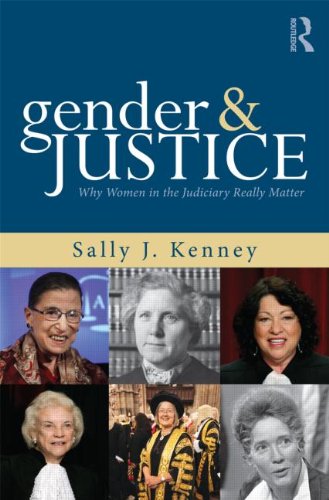

by Sally J. Kenney. New York: Routledge, 2013. 310 pp. Hardback $145. ISBN 978-0415881432 0. Paperback $45.95. ISBN 978-0-415-88144-9

by Sally J. Kenney. New York: Routledge, 2013. 310 pp. Hardback $145. ISBN 978-0415881432 0. Paperback $45.95. ISBN 978-0-415-88144-9Reviewed by Susan M. Sterett, Department of Political Science, University of Denver.

pp.28-30

In the nineteenth century arguments in the United States for including women in politics started with difference arguments. Women were different from men and would do politics differently: kinder, gentler, with care for children, communities and families at the center of what they did. These approaches to politics fall under essentialism, or the idea that there are core differences between men and women. Essentialism has fallen out of favor in feminist theorizing; descriptions of differences in public opinion or voting take gender to be one variable, and find differences by demographic groups in the United States. Still, differences are not ascribed to individual women as members of a uniform class. Essentialism remains in public law scholarship concerning whether women who are judges vote differently from men. While findings are often null, the point is that the essentialist thesis remains a primary genesis of theorizing. Not only are the findings null. Women judges, as Sally Kenney points out, are often adamant that their gender does not explain their judging. They spent all that time getting training and experience, and in the end they are just one of the girls (pp.5-6)? Kenney argues that part of the problem is focusing on outcomes in cases, surely not the only data about the courts that political scientists should care about.

Sally Kenney has a great alternative, pointing out what we know as citizens and often forget as political scientists: judges are public figures and governing officials. They do more than vote in cases. Kenney argues for opening up public law scholarship to a wider understanding of what courts do and mean in political life. They symbolize government, they represent us descriptively, and their appointments may tell us something about how elites are governing. To illustrate: the middle and high school students I once saw dressed their best to see Justice Sotomayor speak about her life and work did not know nor did they care about her voting record as a federal judge. They were thrilled to hear a woman with a background similar to many of theirs who had succeeded in mainstream politics, and who had done so with charm and grace.

Kenney focuses on three different cases to illustrate the ways gender has been significant in getting women on the bench. The appointment of Justice Rosalie Wahl to the Minnesota Supreme Court in 1977 required feminist mobilization, and in turn mobilized joy and hope to those who had worked for the appointment. The appointment of the first woman Law Lord in the United Kingdom in 2002 symbolized modernization in an institution that had long been subject to suspicion as an out of touch arm of the Conservative Party. The appointment of women to the European Court of Justice adds a dimension of representativeness to the judiciary in an institution where [*29] geographic representation had been normal to appointments.

As an alternative to essentialism, Kenney argues for thinking through gender as a process. By that she means for us to consider how we attribute meaning to sex differences. Meaning attribution often devalues whatever women are associated with. Feminist scholarship has turned us to see the work that emotion does in public life, for example, work that many analyses of politics have ignored. To have all the description of the work that gender does in judging be contained in a variable dichotomized as male/female is necessarily essentialist. Kenney’s point comes across well in two cases from the United States that she uses. First, drawing on Linda Greenhouse’s biography of Justice Blackmun (2006), Kenney explains that his work at the Mayo Clinic and living with his daughters convinced him of the importance of reproductive rights (p.40). Second, she contrasts the mobilization of support for the first woman on the Minnesota Supreme Court, Justice Rosie Wahl, with the appointment of Justice Rose Bird on the California Supreme Court. Both were appointed in 1977. Justice Bird was subjected to a retention election in 1986, along with two male colleagues. The retention election was the first California had seen, and Kenney puzzles about the defeat by telling stories of incompetent men who were never subject to a similar fate. Kenney quite rightly points out that both Justice Bird and Justice Wahl were women, and treating them as the same would lead to a conclusion that gender didn’t matter in support for a justice, or that California was less committed to gender representation than Minnesota. She also discusses Justice Bird’s removal in its California context (pp.149-158). Kenney argues that Justice Bird did gender very differently from Justice Wahl, and was treated differently in the press.

Throughout the book, Kenney critiques essentialist frameworks and what has been left out of public law scholarship with a wit that makes a reader laugh out loud, not a common reaction to reading studies of judging. For example, she wonders whether anyone who has ascribed distinctive kindness and gentleness to women has ever spent time at meetings of feminist scholars.

Kenney argues from John Stuart Mill’s perspective: it is wasteful to ignore the talent of half the population. It is also disheartening, contributing to the publicly available belief that women have little to contribute to governing. Kenney also tracks the arguments made concerning the importance of getting women onto juries: it is simply not representation by one’s peers that no women are on significant governing bodies. She answers the argument that pits descriptive representation against merit by pointing out that no one ever raises that argument when people argue for representation by geography, or experience, or field of law. Critics only raise it when race and gender and misrepresentation come up. She raises her most biting points hilariously. In this case, she points out that the convention is that the European Court of Justice includes a judge from each member state. She thinks it unlikely that “[any]body sneered ‘Do you want just any Luxembourgeois judge?’ or inquired whether the Council was supporting him just because he is from Luxembourg” [*30] (p.128). It’s great material to use in asking students to think about diversity and demographic representation.

In the final study in the book Kenney discusses backlash, and the possible retreat in the American states from descriptive representativeness on the courts. In this chapter Kenney provides the extended treatment of Justice Bird of California. She treats cases holistically, and is reluctant to find causal factors when they are so intertwined and the case numbers are often very small.

Kenney has chosen the cases to illustrate the different kinds of work gender can do rather than to generate explanations that are evaluated across cases. The illustrations open more questions than they answer, a hallmark of generative work. She does not argue when people might mobilize to get women on the bench, nor how that might vary across courts or countries. She also does not use the cases to reconceptualize what emotion work is, or what descriptive representation means, or when gender or other diversity might signal something important in politics. The cases do vary along dimensions that almost certainly matter in the different meanings of gender. For example her case study concerning gender and the mobilization of emotions comes from appointment of the first woman to the Minnesota Supreme Court. That’s less likely in the European Court of Justice because, as Kenney explains, the ECJ is not set up for transparency or election of judges. Kenney leaves for other scholars consideration of how we would think about transferring frameworks. What she has left us with is a research agenda and reasons to care about appointment of women to the courts quite apart from differences in voting behavior coded by whether a judge is male or female. Finally, she writes as she wants others to: she cites many women scholars. She doesn’t agree with them all and she treats arguments as worthy of response.

Another productive tension remains. While the book argues powerfully for seeing gender as a social process, or attribution of meaning to sex differences, Kenney argues for women’s appointments to courts as a matter of the responsibility and rights of citizenship. She argues for women with a variety of perspectives on judging, not because appointment would lead to a particular set of outcomes in cases. Arguing for women to be on the courts is indeed focusing on public gender identity in an essentialist fashion. However, so is arguing for a Luxembourgeois judge, and that doesn’t stop anyone.

REFERENCE:

Greenhouse, Linda. 2006. BECOMING JUSTICE BLACKMUN: HARRY BLACKMUN’S SUPREME COURT JOURNEY. New York: Times Books.

Copyright 2014 by the Author, Susan M. Sterrett.