by Yasuhide Kawashima. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013. 189pp. Cloth $34.95 ISBN: 978-0-7006-1904-7. Paperback $17.95 ISBN: 978-0-7006-1905-4.

by Yasuhide Kawashima. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013. 189pp. Cloth $34.95 ISBN: 978-0-7006-1904-7. Paperback $17.95 ISBN: 978-0-7006-1905-4.Reviewed by Staci L. Beavers, Department of Political Science, California State University San Marcos. Email: sbeavers [at] csusm.edu.

pp.83-85

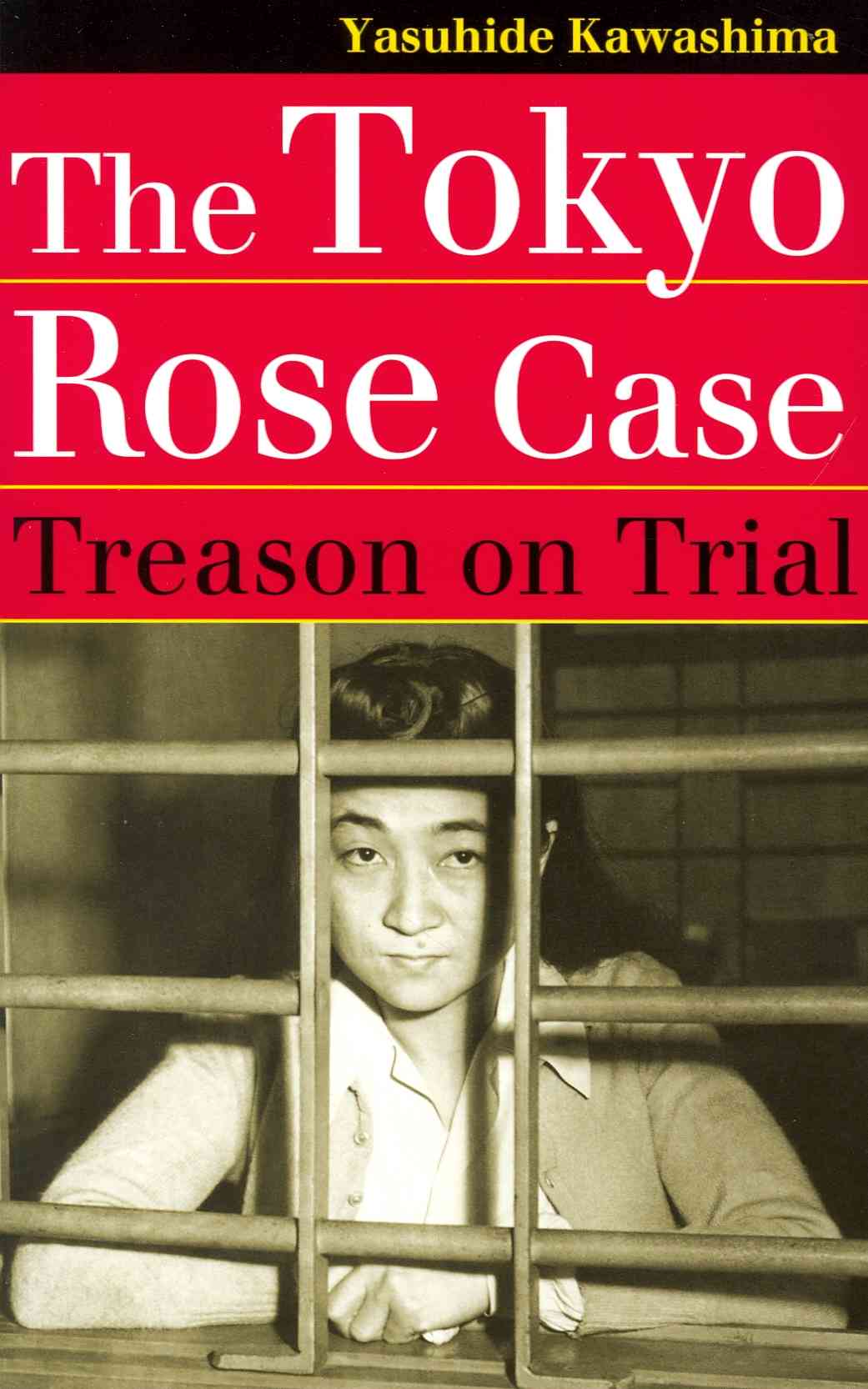

While many Americans might recognize the name "Tokyo Rose" if they ran across it, few are likely to know the tragedy behind the infamous but apocryphal radio moniker. Yasuhide Kawashima's THE TOKYO ROSE CASE: TREASON ON TRIAL introduces a new generation of readers and the broader public to an historically significant failure of the criminal justice system.

Kawashima's brief volume brings to life the heartbreaking story of Iva Toguri d'Aquino. As a young American citizen marooned in Japan during World War II, d'Aquino worked for a time as one of Radio Tokyo's English-speaking radio personalities. She became known to Americans after the war as the infamous "Tokyo Rose," a radio personality who allegedly tortured Allied troops with taunts about the comforts of civilian life they had left behind, the faithlessness of their women, and their poor prospects for winning the war.

Yet "Tokyo Rose" herself never existed, as the stage name was never used by any of Radio Tokyo's English-speaking broadcasters (pp.27-28, 40-41). As for d'Aquino, Kawashima draws on existing accounts to describe her American patriotism while she was stranded behind enemy lines during the war. Her "Zero Hour" broadcasts were scripted by Allied POW's working subversively to undermine Japanese propaganda efforts and broadcast more Allied-friendly entertainment without raising the suspicions of their Japanese captors (pp.29-33). Yet after Japan's surrender, d'Aquino was brought back to the U.S. in military custody, accused of treason for allegedly broadcasting reports and commentary undermining American troop morale. Convicted of treason on one of eight counts in a highly questionable trial, d'Aquino was sentenced to prison, stripped of her citizenship, and assessed a hefty fine that the U.S. government went to great pains to collect. Only after she earned parole and successfully faced down the government's attempts to deport her did a public campaign to win a presidential pardon gain momentum. Yet Kawashima explains how, after an unjust prosecution cost Iva Tugori d'Aquino her freedom, her reputation, her marriage, and years of litigation to fight deportation, President Ford's 1977 pardon provided only a partial restoration of justice for d'Aquino, who died in 2006.

Kawashima appeals for what he argues is a more just resolution: a posthumous exoneration through a court order acknowledging the government's misconduct throughout the case. Fittingly, Peter Irons' trailblazing effort to win writs of coram nobis for Fred [*84] Korematsu and other Japanese Americans unjustly prosecuted during World War II provides the foundation for such a writ here (pp.160-166). However, Kawashima never addresses whether such an option is even available for the deceased, perhaps a doubtful prospect (see, for example, Wolitz, 2009).

While never validating the likelihood of a writ of coram nobis, Kawashima's account does pull together existing research to document misconduct by government officials throughout the criminal investigation, trial, and appeals. For example, trial judge Michael Roche is called out both for willful ignorance and bias throughout the trial proceedings (pp.74-75). Stronger yet is the case for prosecutorial misconduct. Kawashima weaves together previous scholarly accounts to document prosecutors' bullying and intimidation of witnesses – both to encourage prosecution witnesses to take the stand and to discourage prospective defense witnesses from coming to the U.S. to testify (pp.77-78, p.137). More disturbing still is the suppression of knowledge of a prosecution witness's perjury, a conspiracy which Kawashima argues reached all the way to Attorney General Tom Clark (pp.72-73).

While focused primarily on the treason case, Kawashima may actually be most effective in putting a twist on illustrating the human costs of both war and political battles. While many Americans have gained at least a passing familiarity with the plight of the thousands of Japanese Americans herded into internment camps during World War II, here is the story of a Japanese American citizen's experience in Tokyo during that same conflict. An American citizen by birth, young Iva Tugori traveled to Japan for the first time in the late summer of 1941 to visit a sick family member. Bad timing on her part and bureaucratic stymieing by American officials kept in her Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack. Kawashima provides a surprisingly detailed narrative of the young woman's all-American life before her fateful journey to Japan and her time in Tokyo. One of his most intriguing sources is a Japanese surveillance report documenting the American's daily routines in Tokyo, her neighbors' suspicion of the young woman who openly expressed her American patriotism while living in the enemy capital, and even her efforts to collect food and supplies for Allied POWs forced to work at Radio Tokyo (pp.35-37). And just as she was swept up in broader political headwinds when stranded in enemy territory during the war, d'Aquino later found herself caught up in the Truman Administration's post-war efforts to prove itself sufficiently vigilant in pursuing alleged wartime traitors. Kawashima conjectures that treason prosecutions such as d'Aquino's helped put President Truman over the top in the 1948 election (pp.60-61). While his evidence on this point is thin, he does convincingly demonstrate how d'Aquino was swept into a media and political firestorm as fodder for journalists, politicians, and other opportunists willing to trade on another human's suffering. Kawashima opens the book with a statement regarding the "ongoing resonance" of d'Aquino's story (p.xii); he brings that point home most powerfully with a painful illustration of how innocents be can destroyed by media and political battles in which they have little if any say, let alone control. [*85] What could be more relevant in today's acrimonious political climate, fostered in part by the constant bombarding of the human senses with ideologically- and agenda-driven "news" coverage?

D'Aquino's life in prison and the later campaigns to rehabilitate her legal record and her reputation unfortunately earn significantly less attention here. A more complete discussion of the Japanese American community's efforts to win a presidential pardon would have added much to the book. Yet Kawashima draws a stark picture of the limits of a legal pardon for someone who was wrongly convicted in the first place: while it restores the recipient's legal rights, it does not in fact erase the "stain" of guilt itself.

Written for a "general" audience (p.173), THE TOKYO ROSE CASE will likely prove frustrating for the more serious reader. Most significantly, the shortage of direct and detailed citations throughout the text makes it difficult for the inquisitive reader to follow up where questions arise about the meaning of a passage or alternative perspectives on the arguments provided. This will be particularly frustrating for the reader attempting to parse apart the case for the prosecutorial misconduct so crucial to Kawashima's take on the coram nobis issue (pp.66-69, 97). For example, while Kawsahima briefly alludes to the fact that incriminating DOJ memos referring to suppressed evidence were brought to public light only in the 1970s (p.89), the release of such documents is never explained in the text and is still given only the scantest of attention in the brief "Bibliographic Essay" provided at the end of the volume (p.175). The Series Editors make clear the decision to pare down citations was made "to make our volumes more readable, inexpensive, and appealing for students and general readers" (p.173). This puts the book and its author in a tight spot: I would be hesitant to assign the book to university-level students for the reasons noted above, yet the complexities of a case such as this may well be beyond the reach of many k-12 students (and perhaps some "general" readers).

Yet such a harrowing true tale deserves the broadest possible audience, and Kawashima's efforts to make the case more broadly accessible deserve credit. While the law of treason is narrowly drawn and fortunately little-used, the implications of Iva Toguri d'Aquino's treason case are legion. Such a trial depicts a criminal justice system marked by racial bias, prosecutorial misconduct, and lousy judicial oversight. Surely not very uplifting reading, but all the more important in helping today's Americans understand the importance of basic procedural rights in the criminal justice system.

REFERENCE:

Wolitz, David. 2009. "The Stigma of Conviction: Coram Nobis, Civil Disabilities, and the Right to Clear One's Name." BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 2009 (November): 1277-1339.

Copyright 2014 by the author, Staci L. Beavers.