Vol. 28 No. 2 (April 2018) pp. 25-26

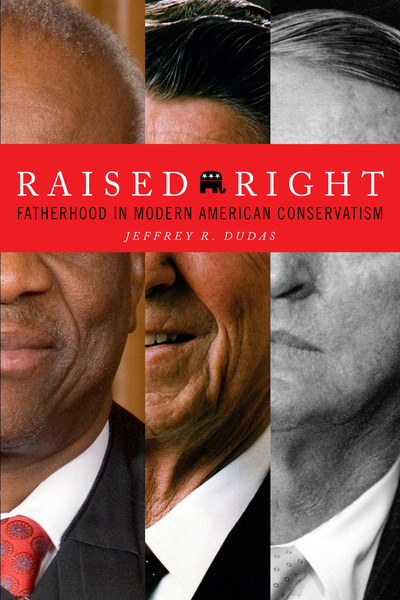

Vol. 28 No. 2 (April 2018) pp. 25-26RAISED RIGHT: FATHERHOOD IN MODERN AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, by Jeffrey R. Dudas. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2017. 207pp. Cloth $24.95. ISBN: 9781503600188.

Reviewed by Anna Kirkland, Department of Women’s Studies, University of Michigan. Email: akirklan@umich.edu.

Fathers and paternal authority are ubiquitous references in conservative political and social thought. Conservatives pay homage to the founding fathers in originalist constitutional interpretation, locate family breakdown in fathers’ abandonment, and seek to bolster little girls’ self-esteem with father-daughter dances. In RAISED RIGHT: FATHERHOOD IN MODERN AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, Jeffrey Dudas argues that fatherhood is far more than a popular hortatory point of reference for political conservatism. It provides an explanation for how such a diverse set of people and ideas have held together politically with such effectiveness for so long. Paternal rights discourse is, he argues, “both [conservatism’s] unifying principle and the primary means by which it covers over its scar tissue” (p. 38). Dudas elaborates on what he means by scar tissue later in the conclusion, observing that “paternal rights discourse . . . constitutes national heroes and enemies; it identifies and orients action against supposedly heteronomous, immature, and subversive people and, in so doing, guilds the fractious tendencies at American conservatism’s core by giving its most devoted practitioners something to believe in” (p. 134). Both religious conservatives and libertarians can agree (for quite different reasons) that single mothers who need social goods such as paid maternity leave or child care support are deviant failures and that a strong father in the home is the best fix.

Dudas constructs the core of his argument based on an analysis of the lives and writings of three of the most iconic and celebrated conservatives: William F. Buckley, Jr., Ronald Reagan, and Clarence Thomas. He extends his argument to analyze the internal tensions within conservatism that also run through the troubled relationships of its heroes with their own fathers, who were repressive, distant, and cruel even as their adult sons define their presence as required for growth into a mature citizen. Dudas argues that an essential conservative assumption is that democratic citizenship requires that children be raised with strong paternal authority coupled with weak maternal authority. In other words, children must both submit to paternal authority but then become self-disciplining. Failures of this process include feminized, narcissistic “snowflakes” who want safe spaces, women who want the government to be their husband, and effete left-wing men who eschew their traditional role. Conservatives see individual rights as having been hijacked by the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, made infantile and coddling, and thus in need of return to the concepts of rights set up by the Founding Fathers. But how, Dudas asks, does the submission to paternal authority end when it is set up to be so complete and total? As he puts it, isn’t it sad to live with this “bone-deep desire for order, stability, and coherence in a world that appears to the afflicted as unstable, out-of-control—a living hell of proliferating, over-determined meanings” (pp. 137-38)? Thus the conservative desire for the dominating father figure is also hopelessly lost in an imagined past, best recapitulated through the private family and gender relations, but always flailing against the changes and variations of the United States we actually inhabit, together, today. RAISED RIGHT, as should be clear by now, is highly critical of conservatism and its commitments, but also acutely sensitive to feelings that Dudas skillfully draws out from his close readings: loss, fear, dissolution, and melancholy. These emotions are not possible for conservatives themselves to acknowledge under paternal rights discourse, and they can only be drawn out by a critical yet highly attentive scholar.

While there are many ways to read this interdisciplinary and wide-ranging book, most [*26] law and courts scholars will likely find the most usefulness in RAISED RIGHT as a cultural analysis of rights discourse on the right side of the political spectrum. It is also an examination of the history of conservative thought in the United States since the middle of the last century, with a focus on the youth experiences and adult jurisprudence of Justice Thomas. After the introduction, there is a substantial chapter detailing conservatism in the U.S. post-World War II, which Dudas uses to set up his argument that it is rights discourse and its underlying commitment to patriarchal fatherhood to explain how all the variations of conservatism have held together. The three middle chapters analyze the writings and thought of each of the three iconic conservative men, showing how tensions inherent in grounding rights in stern paternalism have set up both these individual men and the movement itself for conflict between obedience and self-governance. The book makes a contribution to scholarship in two key ways: first, for its methodological showing of how to do a cultural analysis of right wing thought; and second, for its focus on socio-legal ideas from leaders rather than movement foot soldiers, but in a deeply personalized and literary style rather than through analysis of legal cases or professions. Perhaps the most original aspect of the book is Dudas’s ability to draw out and analyze all the emotions in the texts he analyzes. The book is filled with observations about the longing for authority, the fear and love that a wrathful father evokes in his children, the longing to please, the need for freedom and its uncomfortable co-existence with filial piety, and the melancholy of a world that has left its premodern enchantments behind but is still filled with homesick man-children. RAISED RIGHT is a fascinating alternative to yet another article exhorting liberal elites to try to understand the left-behind angry white voter, and much more successful in its evocations.

The book is beautifully written in an accessible scholarly tone. Dudas draws heavily on literary and cultural studies for his approach, but leaves out the ponderous summaries and jargon one often finds in cultural studies texts. For those mistrustful of this methodological approach, I would advise focusing on the breadth of texts he assembles to make his case (though scholars who look for polling data on conservative attitudes will be disappointed). RAISED RIGHT should be assigned in courses about conservative politics and ideologies for its synthesis of conservatism, its unique cultural studies approach, the new texts it brings into the discussion (particularly the Buckley spy novels, which I never knew about and had not seen written about anywhere before), its readability for undergraduates and beyond, and its fascinating details about the personal lives of Buckley, Reagan, and Thomas. The book would work equally well in Political Science, Women’s Studies, or Ethnic Studies courses covering masculinity, race, and the justifications for hierarchies in contemporary American society. The chapter on Thomas—the one most clearly linked to mainstream legal studies topics—could be pulled out for a course on constitutional jurisprudence, legal theory, or race and American politics. Finally, it is a rare and distinct contribution to gender studies – written by a male scholar in a masculine voice from a clearly feminist perspective (but not heralded as such), entirely about the lives and ideas of famous men and the ways that masculine ideals, emotions, and paradoxes have created so much of our law and politics.

© Copyright 2018 by author, Anna Kirkland.