Vol. 32 No. 7 (July 2022) pp.91-93

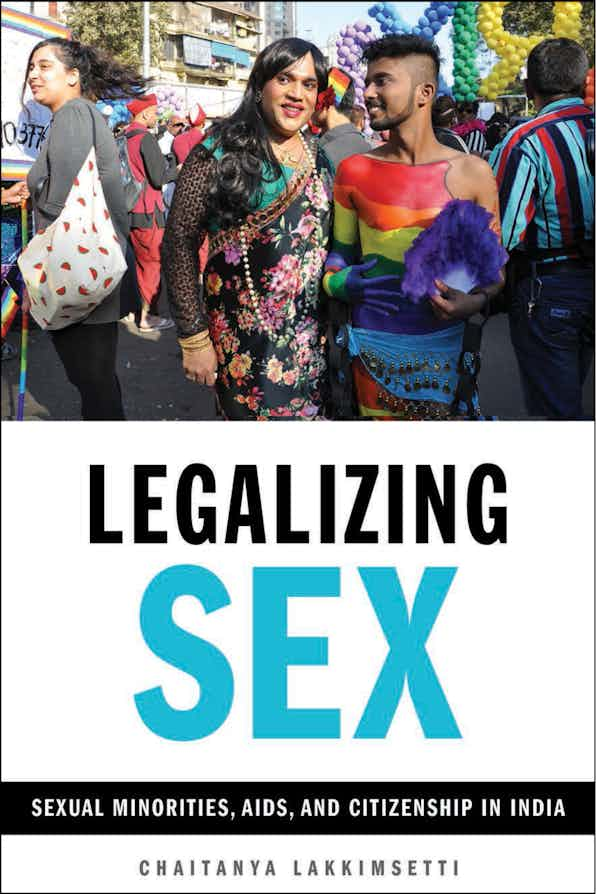

Vol. 32 No. 7 (July 2022) pp.91-93 LEGALIZING SEX: SEXUAL MINORITIES, AIDS, AND CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA, by Chaitanya Lakkimsetti. New York: New York University Press, 2021. pp.199. Paperback $30.00. ISBN number: 978-1-4798-2636-0.

Reviewed by Dhanya Babu. Department of Criminal Justice. John Jay College of Criminal Justice. City University of New York. Email: dbabu@jjay.cuny.edu.

In LEGALIZING SEX: SEXUAL MINORITIES, AIDS, AND CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA, Chaitanya Lakkimsetti explores the experiences of gay activists, transgender communities, and sex workers to understand how biopolitical opportunities shaped the ways that sexual minorities asserted their rights. In order to understand the shared and interconnected experiences and outcomes of activism of these various groups, Lakkimsetti expands the scope of the term “sexual minorities” to include “Men who have Sex with Men” (MSM), Transgender persons, particularly Hijras and Kothis, and sex workers. This well-researched book draws its findings from multiple sources, including twenty months of ethnographic observations, and 85 in-depth interviews backed up by legislative and judicial reports and documents. Lakkimsetti’s book offers a significant contribution that decenters and expands global queer scholarship by drawing attention to the lives of “LGBTKQHI” and sex worker communities in India (p.9). Lakkimsetti uses Foucauldian frameworks of biopolitics and governmentality to understand the intricacies of the state’s regulatory power in relation to the sexually-marginalized communities.

The book offers a beautiful consolidation of five chapters. The first chapter sheds light on the complexities of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s that categorized sexually-marginalized communities as “high risks groups”, especially MSM, sex workers, and transgender persons. The chapter further explores how AIDS shifted the political landscape and the relationship between the state and sexual minorities. Lakkimsetti argues that, as the HIV/AIDS epidemic became an acute crisis that needed the state’s attention, the state’s approach towards sexually-marginalized communities transformed from an exclusionary and juridical imposition of power to a biopolitical partnership.

In the second chapter, Lakkimsetti provides a closer view of the relationship between the state and the sexually-marginalized communities before and after the HIV epidemic. Here, the author provides several accounts of the criminalization and arbitrary violence perpetrated by state agents and experienced by LGBTQHI and sex worker communities. “The HIV/AIDS biopower produces a different relationship between the sexual minorities and the state, one where they are for the first time considered not just as criminals but as partners for these biopower projects” (p.62). However, it was impossible to carry out uninterrupted HIV/AIDS projects without addressing the most immediate problems these communities faced: criminalization and police violence.

Chapter 3, aptly titled “empowered criminals”, is a detailed account of how gay-rights activists and sex- worker communities mobilized to protest and lobby against Section 377 of the Indian penal codethat criminalized adult consensual same sex relationships, and the Immoral Trafficking Prevention Act (ITPA) that criminalizedthat criminalized the purchase of sex. Lakkimsetti argues that HIV/AIDS projects, and the shifts in relationships thereafter, provided a window of opportunity for the sexually-marginalized communities to ask for rights, visibility, and legal reforms. The sex workers collectives and the gay men leveraged and learned from the roles they played in the HIV/AIDS projects to negotiate and fight for their livelihood right and their legal identity. Lakkimsetti describes two contradictory judgments of the Indian Supreme Court in 2013 and 2014 in Chapter 4; the judgments declared non-normative gender identities legal, but non-normative sexual acts illegal. The conflicting nature of these judgments paved the way for more social movements and right-based struggles. The communities were able to use the judgment that legitimized their identity to tactically challenge the other decision which criminalized their sexual acts.

Chapter 5 is an analysis of the 2018 verdict of the Indian Supreme Court that declared Section 377, the criminalization of nonnormative sexual acts, unconstitutional. Lakkimsetti argues that the social movement surrounding sexual rights is interconnected to other social justice goals, including demands for justice among castes, classes, and religions. In this concluding chapter, Lakkimsetti reflects on how the different outcomes of these struggles resonate with transnational and global rights-based activism.

Throughout the book, Lakkimsetti carefully pieced together different events that led to the mobilization of marginalized communities, and how it led to the legal recognition of their rights. This book is a good reference for anyone who would like to understand the developments and trajectory of legal provisions related to sexuality in India. Lakkimsetti’s arguments revolve around highlighting how activists were able to strategically unionize, lobby, and negotiate for their rights while their bodies were under a constant state of scrutiny.

Lakkimsetti’s book and research is undoubtedly an essential contribution to the field of sociological, criminological, political, feminist, and queer praxis’ theories. Yet, some gaps remain unfilled. Although the book is based on comprehensive and thorough ethnographic observation, and 85 in-depth interviews carried out between 2007 to 2015 across India, including Delhi, Bombay, Chennai. The sections of the book that discuss the findings from interviews in Bengaluru, Kolkata, Hyderabad, and Rajahmundry are limited. The majority of the book reflects the legal and political discourses in relation to the sexual rights and HIV/AIDS epidemic. The stories of the interviewees that made it into the book do provide an enlightening insight as to how members of the marginalized communities ascribe to the social movements, state power, and their rights. Given the extensive, long-term ethnographic research the author conducted, it would have been helpful to offer a few more stories or extended vignettes.

Lakkimsetti highlights the idea that these social movements presented both opportunities and challenges influenced by local and global scenarios, either of which could be strategically used to advance the political goals. Lakkimsetti was successful in identifying and exposing the shared struggles of the communities she focused on: the MSM, sex workers, and the transgender communities. Still, despite their shared efforts and experiences, some factors and experiences differentiated each community from the other. The author devotes little attention to these differences. For example, as Lakkimsetti points out, HIV/AIDS activism worked a little less for the sex workers than it did for gay- and transgender-rights activists because anti-trafficking discourses stood in the way of sex workers’ rights. This book could have benefitted by expanding on the areas in which the trajectories of the social movements of these distinct yet similar communities converged and also diverged.

Overall, this book provides a sense of a success story; a story of “how previously marginalized groups found their voices and successfully mobilized for their rights in contemporary India” (p.2). However, some questions still remain unaddressed. Illustrating these rights-based struggles as a success also implies violation of sexual rights and gender identity rights as a phenomenon of the past. Even though Lakkimsetti provides a thorough description of the state violence and discrimination experienced by the queer, and the sex workers communities before, and during the HIV/AIDS projects in India; It is important to acknowledge that, arbitrary arrests and police violence experienced by these individuals continue into the present. Nevertheless, she has fittingly critiqued the most recent Transgender “protection of rights” bills in India by pointing out the constrain the bills place on a transgender person’s right to self-identify their gender. Nevertheless, this book does highlight the movement for sexual rights as powerful and ongoing. One of the significant contributions of this book is the decolonization and decentering of sexual rights discourses and research surrounding queer scholarship via its provision of non-western accounts to a field that has a dearth of information on social movements, identities, and legal developments of queer lives from non-western regions. This book, therefore, is a fresh addition to all the fields that this research is related to.

© Copyright 2022 by author Dhanya Babu.