by Conor Gearty. Polity, 2013.160pp. Hardcover $64.95. ISBN: 978-0-7456-4718-0. Paper $19.95. ISBN: 978-0-7456-4719-7.

by Conor Gearty. Polity, 2013.160pp. Hardcover $64.95. ISBN: 978-0-7456-4718-0. Paper $19.95. ISBN: 978-0-7456-4719-7.Reviewed by Angela Mae Kupenda, Professor, Mississippi College School of Law.

pp.506-509

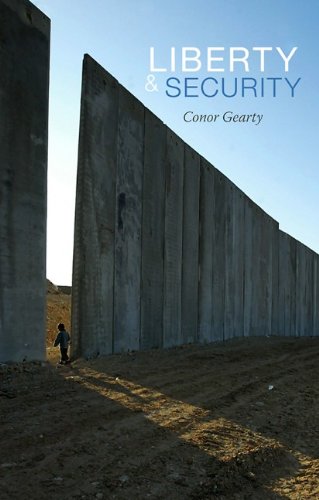

LIBERTY & SECURITY, authored by Human Rights Law Professor Conor Gearty, is a book that is relevant and fills a void through the question it explores. Gearty, while admitting that the terms liberty and security are susceptible to a host of meanings, does not seek in this book to define a more precise meaning for these terms. Rather, the book focuses on the “for how many” question (p.2). Gearty asks and answers whether liberty and security are “to be for all or just the few?” His first chapter phrases and rephrases the question to press the reader to consider whether societies that are walled up to provide security for some are indeed “blatant efforts by the ‘haves’ to shut out not only the sight of the ‘have-nots’ but also any opportunity the unlucky many might have to glimpse what a better future would look like” (p.3). While humans do not necessarily disagree about the value of liberty and the value of security, the difference lies in deciding who should benefit, and how many should benefit. While Gearty urges us to consider the societal impact of the way people answer these questions, Gearty adopts a position of universality. Liberty and security should belong to all rather than to just a few.

Further, Gearty identifies as allies to the goals of liberty and security for all: democratic government, the rule of law, and respect for human rights. The chapter, “Struggling towards the Universal,” illustrates the dysfunction present with the application of principles of democracy and the rule of law. The argument is that, rather than seeking liberty and security for all, those empowered seek to preserve themselves at all costs. As a result, just as for some democracy, liberty and human rights abound, for others so do poverty and inequality. Hence in practice liberty and security evaporate, as the practice of them both is a selective practice that is unchallenged, or is even embraced as an appropriate selective practice in our society. The same occurs with human rights as they are selectively applied. The book persuasively urges that this selective application and denial to the have not’s reveals “the creature of a grand bargain between capitalism and its ideological opponents” (p.27). So rather than serving as a check on each other, these systems perpetuate a status quo that offers the have not’s a few extra crumbs to keep them placated so they participate in the system and do not challenge it.

While societies then vocally urge for consistent, stable rules of law and reliable principles of human rights, in application these same societies deny them both to their have not’s. This denial in practice, then, makes the challenge to these abstract principles even more difficult. As I read and reviewed this book, I continuously made notes in the margins about the contemporary problems in America, [*507] even in the year 2013, that are illuminated by Gearty’s arguments. For example: the legal justifications of the killing of unarmed youth who are perceived to be a part of the unprivileged; the lesser value the law in its application places on the security, bodies and lives of those who are outsiders to affluence; and, the rule of law that allows and encourages the unabashed racial profiling of innocents to make the ruling class and the economically endowed feel more secure.

Gearty mostly applies his critique to the global stage. While applauding the United Nations for its past commitments of a broader understanding of liberty and security to be applied more widely, this book details the changes in UN policies that suggest a narrowing of the UN principles so that they will not apply to all. As examples, Gearty questions the failure of the UN to provide guidance of what “terrorism” means, and claims the UN has sought to make some feel more secure while threatening the liberty of others. The argument is that systems imposed by the UN and numerous countries currently are outside the rule of law as they provide only “pseudo due process” and pretend to care for all while not actually doing so through the use of blacklists, secret closed trials, and the curtailment of human rights justified by the broad use of the threat of terrorism.

Chapter 5, “A Very Partial Freedom,” is a detailed account of President George W. Bush’s reaction to 9/11 and how his decisions precisely communicated to most Americans that the curtailment of freedoms would not apply to them, while the more secure environment with these curtailments would inure to their benefit. This group of Americans, then, did not immediately fear the intrusions upon the rule of law, democracy and human rights, as they were sure their rights as privileged humans (based on whiteness, citizenship, class, religion) would prevail. This chapter tracks the President’s military response. While Bush was a controversial and much criticized president, his decline in popularity seemed to be based on the economy and not on his war policies, his curtailment of human rights, and his frequent rejection of the rule of law. This chapter discusses the detention camps and black holes, where the rule of law did not enter or prevail, torture principles that escaped being labeled as human rights violations, and the use of military commissions that avoided rule of law principles of due process ordinarily available in the United States. Gearty’s theme is that “the many” were Americans who needed not to fear, for the human rights violations would not put them at risk and the rule of law violations made them feel more secure. At the same time, this was a partial freedom, for those who stood outside the privileged gates were more at risk at suffering from deprivations of liberty and security.

This very well written book was a concise read. I also see it as potentially an excellent pedagogical supplement for both core courses and also seminar courses. This book could be assigned for a constitutional law seminar after a professor, for example, covers the presidential authority cases, especially those post 9/11.

In addition, for those who are studying comparatively other countries and systems, such as South Africa, this book could be studied to compare/contrast [*508] how the few controlled the many and used the rule of law to lock out the many nonwhites during apartheid. This book, thus, could be accompanied with a read of one of Nelson Mandela’s books, especially as to Gearty’s theory about how a government, the prevailing rule of law, and human rights violations operate together to deny security and liberty for some. Comparably, Mandela described, “the policy of the government which was ruthless and very brutal and you have to go to jail to discover what the real policy of a government is” (Mandela, p.253).

For those who are studying the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South of America, Gearty’s book could also be a provocative accompaniment, for example, to the study of the written work of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Especially relevant here is Gearty’s final chapter which proposes solutions for reaching universal notions of liberty and security. I was fascinated by Gearty’s argument that those who are in denial, or in “collective self deception” (p.112) about “the lack of liberty and security for all” may be on a first step toward universal principles. He argues that this collective self-deception or “hypocrisy is a route to critique which can in turn be managed into a passageway for change” (p.112). Or, in other words, those who find it necessary to deceive themselves about the availability of liberty and security, may be one step away from being able to critique selective systems that they are actually ashamed of (and which leads to their self deception). Analogously, Dr. King rejected tokenism for a few as an illicit tradeoff for widespread change and equality (King, pp.17-18). Thus the self-deception, explained by Gearty, is fruitful only if it leads to change. Self-deception as a place of permanence, though, perpetuates the societal norms of liberty and justice for the “have’s” and not for the “all.”

Finally, for those who incorporate film in their classes, Gearty’s book would be an excellent read before or after classroom viewings of the film IN TIME. This action film depicts a future society where “time” is the currency of exchange. The have’s inherit more time, while the have not’s struggle to just live to the next day. Moreover, as suggested by Gearty in discussing our societies even of today, the societies of In Time are separated by space so that the have’s do not even have to look upon the have not’s, nor can the have not’s get a visual glimpse of a better life.

Gearty’s book cover, even, depicts a future break in the walls as a hope. The cover shows a small child standing in the narrow gap of a fenced wall that, perhaps, protects some from the other, or rather provides appearances of liberty and security for some while denying the same to the other. It seems the child represents the hopes that one day walls will be dismantled that define who is entitled to liberty and security, and that liberty and security, through democratic governments, the rule of law, and predominant human rights will then prevail for us all.

REFERENCES:

IN TIME. Twentieth Century Fox. 2011.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1963. WHY WE CAN’T WAIT. New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc. [*509]

Mandela, Nelson. 2010. CONVERSATIONS WITH MYSELF. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Copyright 2013 by the Author, Angela Mae Kupenda.